- Evidence that bio/medical postdocs cannot get jobs in academia

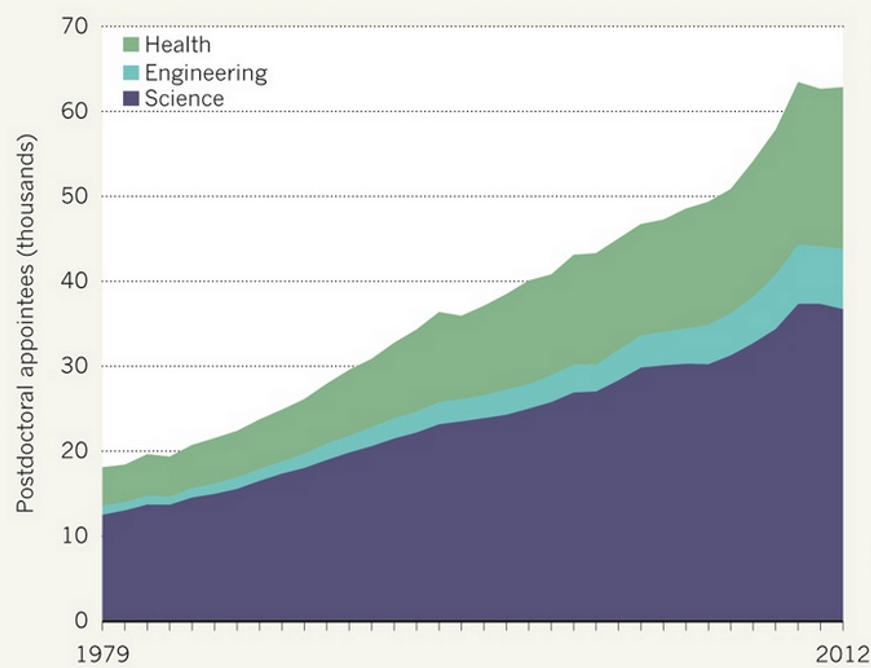

A typical summary article mainly looking at the USA is [https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/too-many-postdocs-not-enough-research-jobs/2017415.article]. “The number of biomedical graduate students in the US nearly doubled between 1979 and 2009, to 56,800. The NIH estimates that the current number of bio/medical postdocs – who have already received their degrees but who continue to languish on campuses – could be as high as 68,000. That has meant a steady supply of people to work in the labs of senior scientists, which is considered a traditional step in the progression from doctorate to research career. But it has also caused that step to be extended. Postdocs who finally obtain university positions – and this has declined from 34% of people with biomedical PhDs in 1993 to 26% today – are now, on average, 37 years old, the NIH says. And they do not receive their first research grants until they are 42, compared with an average age of 34 in 1970.”

An NIH report [https://www.nap.edu/catalog/18982/the-postdoctoral-experience-revisited] suggests “the growth in the number of postdoctoral researchers far exceeds the growth in the number of tenure-track job openings“.

- Evidence for the postdoc pyramid

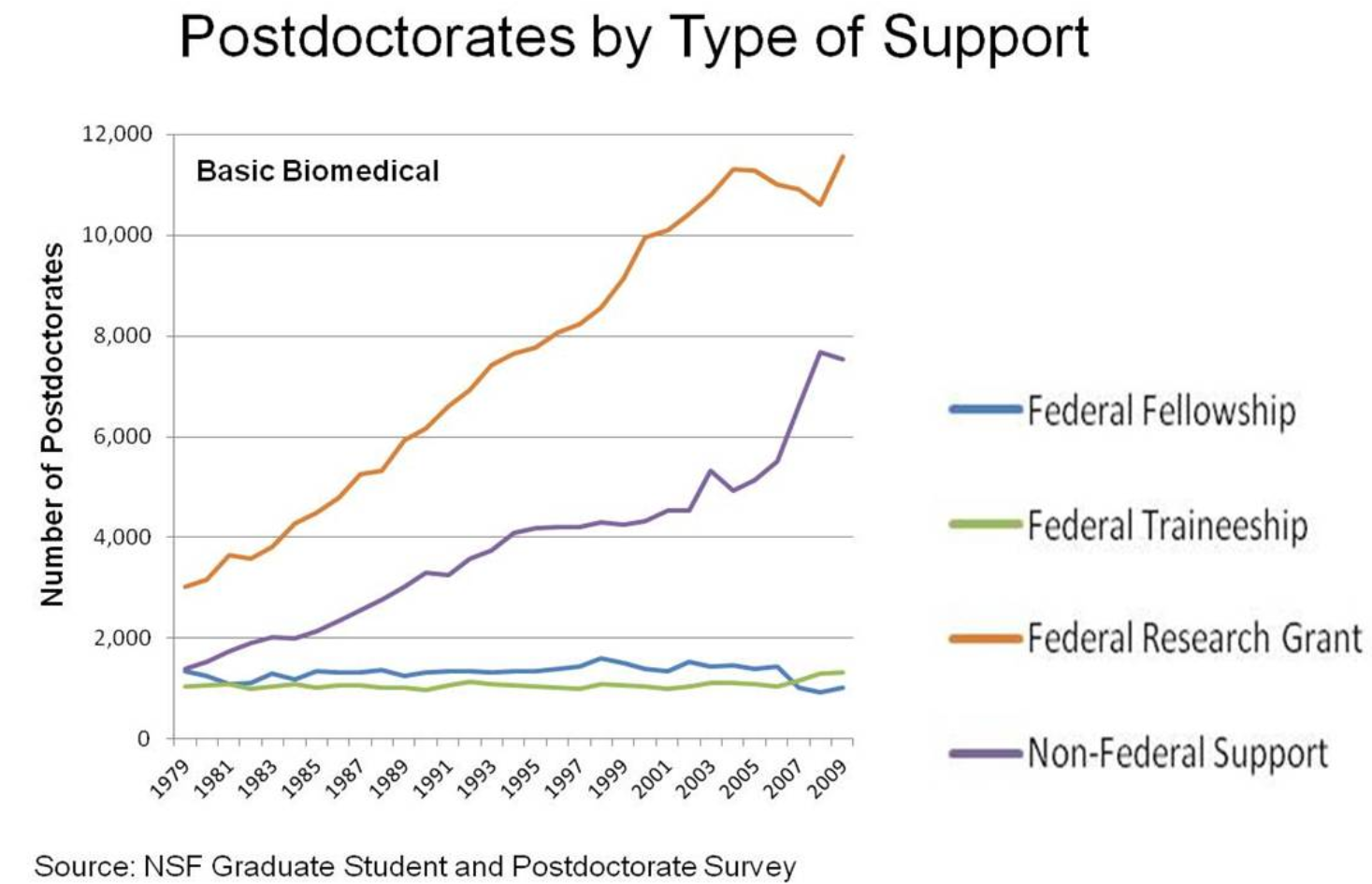

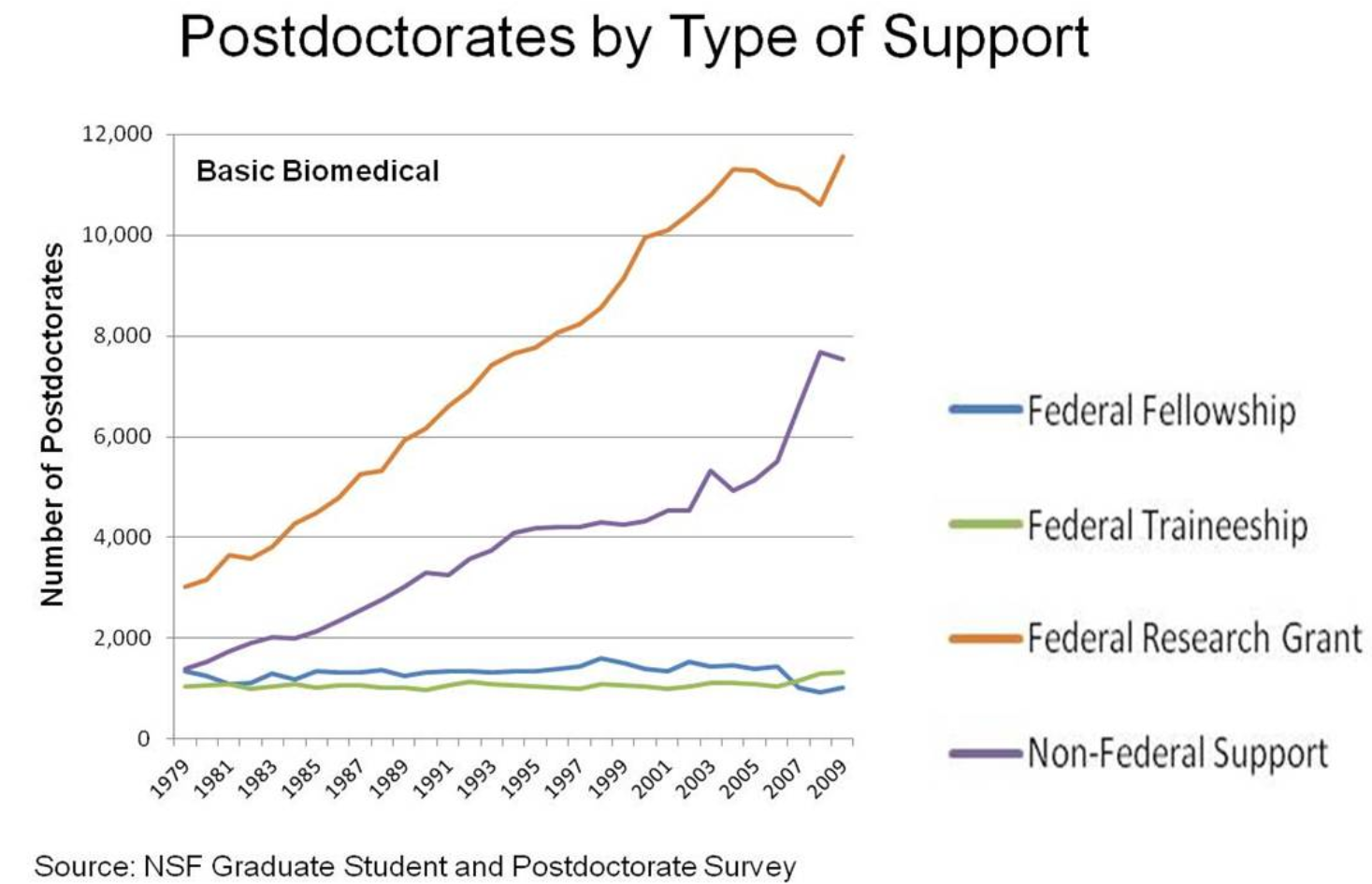

From the USA, an NIH report on increase in postdocs is [https://nexus.od.nih.gov/all/2012/06/29/postdoctoral-researchers-facts-trends-and-gaps/]. [from NSF: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind14/index.cfm/chapter-5/c5h.htm#s4].

[from NSF: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind14/index.cfm/chapter-5/c5h.htm#s4].

Also see a discussion about how to solve excess PhDs in the biomedical sciences [http://www.nature.com/news/how-to-build-a-better-phd-1.18905].

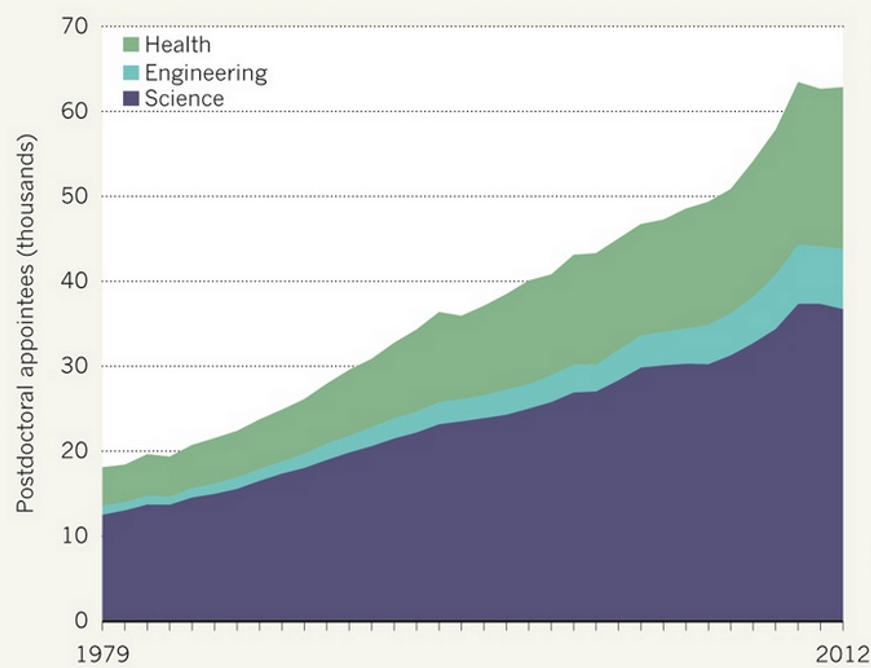

For numbers of postdocs, see [http://www.nature.com/news/the-future-of-the-postdoc-1.17253], which compares with the OECD total number of HE researchers in USA as 200,000 in recent years. It suggests “whereas about 65% of US PhD-holders continue into a postdoc, only 15–20% of those move into tenure-track academic posts. The European situation is even more competitive — in the United Kingdom, for example, about 3.5% of science doctorates become permanent research staff at universities“. This shows most postdocs work in the science areas.

This shows most postdocs work in the science areas.

The number of PhD students per academic in the USA is discussed in [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4309283/] which also discusses feedback loops in operation here. This can be compared to the number of faculty in the USA [http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1756&context=articles] which shows around 550,000 in 1990.

In the UK, the RAE2008 [http://www.rae.ac.uk/submissions/download.aspx?option=uoa] gives the total number of chemistry postdocs about 60% higher than the number of academics, while in physics the number of postdocs on average is about the same as the number of permanent staff. More generally in the UK, HESA data [http://www.hesa.ac.uk/] shows that for fixed-term contracts (postdocs mostly) there is about half the number compared to permanent academics. This is probably heavily skewed away from non-science subjects where postdocs are much rarer.

- Turnover of academics

In the UK there is some data from 2001 on turnover in universities [http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130401151715/http://www.education.gov.uk/publications/eOrderingDownload/RR658.pdf] which suggests something near 10% annual turnover rates (but this includes contract research staff, and possibly postdocs), but is very similar to general levels in professional employment. It is apparently higher (15%) for science subjects (which have more contract staff). It apparently increased from 3% in the early 1990s (a figure which does not include contract staff). For those on permanent contracts, there was +7% in, and only 2% out (and 2% retired/died). Thus a figure of 2-3% annual turnover among permanent academics seems more likely.In Germany turnover is even lower, as faculty are not expected to move once they have a permanent position, and the framework is designed to reinforce this.In the USA, data from the 1980s-90s shows permanent professor turnover as larger, around 8-10%, possibly reflecting the larger number of universities in the USA, and their array into hierarchies.

- Are scientists happy?

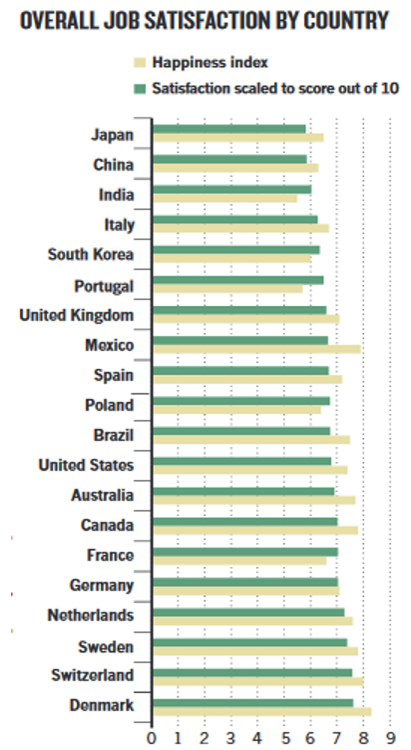

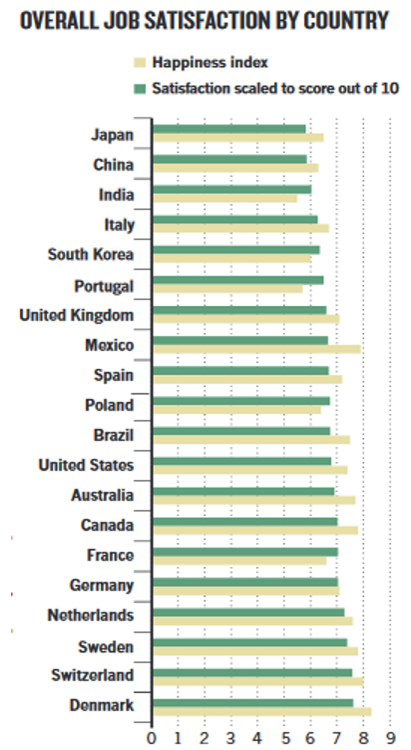

There has been discussion of a happiness index for scientists [http://www.nature.com/naturejobs/science/articles/10.1038/nj7413-685a] but little work on this. [showing ‘job satisfaction’ of scientists]. Happiness is known to be strongly correlated with affluence, across all countries (both between and within). Thus it might be expected that scientists would show similar correlations, with perhaps research income being substituted for personal wealth.

[showing ‘job satisfaction’ of scientists]. Happiness is known to be strongly correlated with affluence, across all countries (both between and within). Thus it might be expected that scientists would show similar correlations, with perhaps research income being substituted for personal wealth.

While there are definitions of “Happiness Index” for a society, it is not clear a robust equivalent has been measured for scientists. For instance, is it rising or falling among scientists?

- Are children of scientists more likely to become scientists?

Family ‘science capital’ is key a recent report finds [http://www.kcl.ac.uk/sspp/departments/education/research/aspires/aspires-final-report-december-2013.pdf]. “We found that families exert a considerable influence on students’ aspirations. This influence operates in many ways, but a key factor affecting the likelihood of a student aspiring to a science-related career by the age of 14 is the amount of ‘science capital’ a family has. Science capital refers to science-related qualifications, understanding, knowledge (about science and ‘how it works’), interest and social contacts (e.g. knowing someone who works in a science-related job). Science capital is unevenly spread across societal groups. Those with higher levels of science capital tend to be middle-class – although this is not always the case, and not all middle-class families possess much science capital. Students from families with medium or high science capital are more likely to aspire to science and STEM-related careers and are more likely to plan to study science post-16. Longitudinal tracking showed that students with low science capital who do not express STEM related aspirations at age 10 are unlikely to develop STEM aspirations by the age of 14.“

[from NSF: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind14/index.cfm/chapter-5/c5h.htm#s4].

[from NSF: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind14/index.cfm/chapter-5/c5h.htm#s4]. This shows most postdocs work in the science areas.

This shows most postdocs work in the science areas. [showing ‘job satisfaction’ of scientists]. Happiness is known to be strongly correlated with affluence, across all countries (both between and within). Thus it might be expected that scientists would show similar correlations, with perhaps research income being substituted for personal wealth.

[showing ‘job satisfaction’ of scientists]. Happiness is known to be strongly correlated with affluence, across all countries (both between and within). Thus it might be expected that scientists would show similar correlations, with perhaps research income being substituted for personal wealth.